-

The Fictional Einstein

What’s true for almost all famous people, is true for Albert Einstein: the typical conceptual images of him are a blend of fact & fiction.

Just consider the case of what he is said to have said. Recall that he is endlessly quoted as an authority on almost any topic. Yet, many of the quotes are not, in fact, by him at all. For example, special interest groups misquote him, wanting to embrace him as the poster-boy supporting their causes. Here is a short list: he was not home-schooled as a child, not a slow learner, not a vegetarian, and not left-handed. Also, for some strange reason, he is often erroneously quoted as making pronouncements about money matters. But he did not say that “compound interest is more complicated than relativity,” or that “preparing a tax return is more complicated than relativity”– along with other peculiar variations on this economic theme. Many more misquoted-quotes will be found in Alice Calaprice’s delightful book, The New Quotable Einstein (Princeton University Press, 2005).

In non-fictional writings on Einstein, one would expect a certain level of scholarship so as to avoid downright errors and common myths. But what about the category of historical fiction? To be sure, it is well-recognized that there is a persistent tension in historical fiction between authenticity and invention. So, what are the limits of the imagination imposed upon the authors? At the very least, I believe, it’s reasonable that they should avoid saying things that contradict documented facts.

I believe these problems around ‘the fictional Einstein’ are important enough to be brought out into the open, and I hope this brief look, with some examples, will trigger further contemplations and conversations.

The category of historical fiction encompasses (at least) theater, opera, cinema, television, and (of course) literature. There are many plays where Einstein is a character. Two operas. Several movies. On television in 2017, on the National Geographic channel, there was the entertaining TV series, Genius that began with 10 episodes on Einstein’s life (the second series was on Picasso). The Einstein series was an engaging and entertaining look at his life, with a good cast of actors. The sympathetic portrayal of his first wife, Mileva Marić, was especially welcomed; however, it was marred by an overemphasis on her malformed foot (with endless focusing, literally, of close-up shots on that foot) and her subsequent physical limp. In addition, there was almost an obsession with Einstein’s sex-life – no doubt, pandering to the TV audience. The facts were basically true, although it was overdone; and I would question one escapade: I don’t believe that he had sexual relations with his first real girlfriend, Marie Winteler, knowing what we know about her and her family. Put simply: they were living in the late-19th century, not today.

And then there are the specific factual errors throughout the 10 episodes, which are too numerous to mention. Gladly, they are mainly minor, but still irksome, for they could have been avoided if a knowledgeable person had proofread the screenplay. Here’s a partial list. His best friend Besso was not a fellow student at the Swiss Polytechnical School (ETH) with Einstein; Besso was already a graduated engineer with a job in a machine factory when they first met. Mileva did not get pregnant when he was a student at ETH; he gradated in 1900, and their illegitimate daughter, Lieserl, was born in January 1902. His 1905 paper on relativity did not contain the actual equation E = mc2; he didn’t use that later-famous format until 1907. He did not get the idea of a 4th dimension from Carl Jung; Hermann Minkowski (his former ETH math teacher), in a famous lecture in 1908, reformulated relativity theory using four-dimensional math. And so it goes, right up to the last episode that has Einstein teaching at Princeton University, which is not true; instead, he worked nearby (with no teaching duties) at the Institute for Advanced Study, an autonomous institution also (of course) in Princeton, New Jersey.

An exemplary case of Einstein in the movies is the 1994 film I.Q, starring Walter Matthau, Meg Ryan, and Tim Robbins. From the start this work is a comedy, often clever and funny, but having no pretence of being even a bit true or historically accurate. In his 22 years living in America, Einstein lived with his second wife, Elsa, his secretary, Helen Dukas, his sister, Maja, and his daughter-in-law, Margot – although not all at once. Elsa died in 1936, and Maja in 1951. My point is that there never was a niece living with him, although that’s the role for Meg Ryan in the film. The plot has Uncle Albert, along with help from his mathematician friend, Kurt Gödel and others, being a matchmaker for the niece. Although therefore the movie is completely fictional, Walter Matthau’s demeanor and delivery of the character is not far from how I would guess many Einstein scholars might picture Einstein in their minds. Gödel, however, is something else; we know he was very shy and reclusive, nothing like the outgoing character in the film. In the end, perhaps, we could call this ‘Einstein’ not only fictitious but frivolous too.

Fictitious, frivolous – how about fabulous? – as meaning: belonging to a fable, or a serious but made-up story? This brings me to the famous opera premiered in 1976, Einstein on the Beach, by Philip Glass: a work almost 5-hours long, that has no storyline and no plot, and where Einstein as a person does not appear. So, why the title? Supposedly the idea was to incorporate symbols from his life into the work’s scenery, characters, and music; and, as such, the audience is expected to construct personal connections with Einstein. Glass specifically points to what he calls three images from Einstein’s life: trains, clocks, and spaceships. The first two are correct; but spaceships were not a part of his imagination throughout his life. Spaceships, of course, are today associated with relativity in the popular mind, and accordingly with Einstein too. But that happened only after his death.

Consider two specific examples of how supposedly Glass connects his opera to Einstein. The first example is the opening 4-minute choral piece accompanied by an electric organ that consists primarily of the singers repeating this sequence of the numbers 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, either in full or in part, such and 1,2,3,4 or 2,3,4,5,6, etc. Anyone familiar with the music of Glass knows that his hallmark format is repetition and variation, with the music seemingly going endlessly in circles. For this opera, Glass explains that the numerical repetition is a reference to the mathematical breakthroughs that Einstein made. I leave it to the scientific reader to make sense out of this statement, since those numbers are mere arithmetic, whereas relativity used geometry, algebra, calculus, and ultimately tensor analysis. But maybe more importantly, this raises the question as to whether the common opera lover will in any way achieve an insight or make an imaginative leap to an idea about Einstein when hearing this music – independently of the fact that it is often quite beautiful and haunting.

The second example is Act 1, Scene 1, called Train, which is a little under 20-minutes long. The title alludes to Einstein’s use of trains for explaining the theory of relativity to a popular audience: comparing how someone on a moving train measures, e.g., time, with someone on a passing embankment. So, how is this presented in the scene? The most obvious case is clear from the start: on the stage and in the background is a large train, which slowly moves from right to left throughout the scene. Beyond that, for this viewer, at least, I could find nothing in the repetitious music or the characters moving strangely about over the stage that in any way brought to mind Einstein. It made me wonder, again, how other viewers, without the knowledge of Einstein that I have, could make a personal connection with him, as Glass intended – both here and probably throughout the very long opera. Fabulous, indeed.

Finally, we have the most important class: the historical novel. Let’s start with a work that is often cited as an example: namely, Einstein’s Dreams, by Alan Lightman (Warner Books, 1994), a beautiful little book, but ultimately a peculiar work. It is set in 1905 in Bern, Switzerland, when Einstein was working in the patent office with his friend Besso. It consists of 30 very short chapters, dated from April 14 to June 28, each being a dream about a world with a different concept of time. In addition, there is a Prologue, three Interludes, and an Epilogue. (It should be pointed out that it was during this period of Einstein’s life, specifically from March 18 to September 27, 1905, that he submitted five revolutionary physics papers to the German Physics journal. In particular, on June 30, he sent the first paper on relativity that put forth his new theory about time.)

In the Prologue, Einstein is waiting for a secretary to arrive, since he has a paper on relativity for her to type. In the Epilogue, he gives her the paper. In the Interludes, Einstein is with Besso: going for a walk, in a café, and fishing from a boat on the river. In these episodes, Einstein is absent-minded, even moody, distant, and almost incommunicative. There is very little real engagement between them – this, despite the fact that Einstein thanked Besso, and only Besso, for his help with the landmark paper on relativity. (Lightman doesn’t mention this.) Importantly, there is no discussion about the concept of time between them, even though historians have evidence that something Besso said was a catalyst for the idea of the relativity of time. (Lightman doesn’t mention this, either.) Also, there is a brief mention of Einstein’s wife and son, but otherwise nothing on his life. In the 30 chapters of dreams, different concepts of time are considered. For example: time going in a circle, time standing still, a world without time, time going backwards, a world where people live forever, a world without a future, and so forth. Only one dream, on May 29th, where time slows down as people move faster, has any relevance to Einstein’s theory.

Now, importantly, there is no evidence that Einstein ever even considered the other 29 concepts on his road to relativity, nor that such ideas would even emerge in terms of the problems he was working on. I find this all extremely odd. Lightman could have carved out these lyrically written fantasies about other worlds with other concepts of time, without bringing in Einstein at all. That’s why I call this book beautiful but strange. Why he wrote it this way, I don’t know. Moreover, the scope of the novel is only this very short period (two months, however important they were) in Einstein’s life. I therefore cannot categorize this little book as an Einstein novel in any meaningful sense of the term. It’s more fantasy than history; another fabulous story? At least, it certainly cannot be considered an Einstein novel in any comprehensive sense.

And this brings us back to the original category: the historical novel. One would think that there would be a plethora of novels on Einstein, given the popularity and importance of his life, work, and image. In fact, you will find it said that, indeed, ‘there are many novels about Einstein’ – just like all famous historical figures; however, such generalizations are never followed with evidence. I’ve been told that there are such works in some other languages, but I submit that you will be hard-pressed to find many. An Internet search by several Einstein scholars for historical novels on him in English came up empty-handed, except for two very recent books. (I would be grateful to any reader who could point me to any other book.)

Most interestingly, both novels were independently being written around the same time, and unbeknownst to each author. (In full disclosure: I am one of them.) The first to appear was Albert Einstein Speaking (Canongate Books, 2018), by R. J. Gadney. An artist and academic, Gadney published several books (fiction and non-fiction) and wrote several screenplays. Sadly, the Einstein novel was his last work: he died in May 2018. Accordingly, I never got a chance to correspond with him, since I was not aware of his book until early 2020.

Gadney’s novel has 5 chapters. Chapter 1 (the shortest in the book) takes place on 14 March 1954, on Einstein’s birthday, a year before he died. It centers on an accidental wrong-number phone call from a 17-year-old Mimi Beaufort, and an ensuing conversation with Einstein, who answers the phone and begins a relationship with her. She appears again in the final chapter. The core of the book, however, is a well-written historical narrative of his life in chronological order.

Chapter 2 begins with his birth in Ulm, Germany in 1879 and covers the major events over the next 26 years. For example: the birth of his sister, Maja; his father’s gift of a compass that so influenced his thinking about how the physical world works; his pre-teen deep, but brief, religious phase; his early teenage fascination with geometry and algebra; and so forth – up through his studies in physics at ETH in Zürich, where he met his first wife, Mileva Marić, the birth of Lieserl, their marriage (1903) and the birth of the first son, Hans Albert (1904), and finally his job at the patent office in Bern.

The emphasis here, and throughout the book, is on Einstein’s personal life along with political and social issues (such as the ever-present anti-Semitism) – with a focus on his foibles and personal peccadilloes – rather than scientific matters. It’s a fast-paced novel, written in relativity short declarative sentences, conveying seemingly all the key events in his life. The snappy dialogue is reminiscent of a film noire screenplay.

Chapter 3 (the longest in the book) begins with an epigraph that is a quote from Mimi Beaufort on Einstein. It is 1905, the so-called annus mirabilis (miracle year), when Einstein wrote those five papers that changed physics for the rest of the century. Gadney conveys their content in a conventional discussion of what they each entailed, although the emphasis in this chapter is on his relationships with friends and family as he moved from different university jobs in Zurich, Prague, and finally Berlin. Covering the period up the 1933, when he moved to America, this chapter deals with much turmoil and torment in his life: his divorce from Mileva; his marriage to his cousin, Elsa; his celebrity status when his general relativity theory was confirmed in 1919 and he was cast as the next Newton by the news media; the subsequent attacks on his theory by German scientists who called it ‘Jewish Physics’; and, his growing involvement in the budding Zionist Movement. Here, as elsewhere, although much of the dialogue is fictional, there is a liberal use of real things that he said that can be documented. There are also occasional long quotations (from letters or documents or passages from books he is reading).

Chapter 4 also begins with a Beaufort epigraph about Einstein. Although covering the rest of his life, now living in America, it’s a very short chapter telescoping much of what happened, and being entirely on personal, social, and political issues (with many long quotations), such as his harassment by the US government accusing him of being a Communist sympathizer. There is no mention of his obsession with the quest for what he called his Unified Field Theory, which he pursued continuously and endlessly.

Chapter 5 goes back to the beginning in Chapter 1, namely Einstein’s birthday in 1954 and his relationship with Mimi, who along with her sister, Isabella, visit him and meet Gödel and Robert Oppenheimer, who was then the Director of the Institute where Einstein worked. The sisters even go sailing with Einstein, with his boat capsizing so that they have to save him from drowning (since he couldn’t swim). The book then ends with his death a year later.

Gadney has a gift for teasing out what Einstein was thinking and feeling. There are notable descriptions of scenes and places in the novel, as well as background material on politics, society, and the arts. Some highlights: the reconstruction of young Albert’s arguments with his teachers in elementary school; and the dialogues involving the breakup of his marriage to Mileva, and the bickering between he and Elsa. As well, there are about 38 relevant photos distributed throughout the text.

I will not be so audacious as to pick out the minor errors and such in the text, since the author does not have the opportunity to respond. But I do feel it’s appropriate to talk about the opening and closing sections as they relate to the topic here: namely, historical fiction. It’s well-known that as an old man Einstein liked the company of children, and that is what these sections are about: yet his relationship with Mimi that comes about from the wrong-number phone call was clearly fictious from the beginning. It’s a clever and delightful way to begin and end the book: first, it draws the reader in, and then amiably, let’s it go. But here’s my gripe. In the final chapter, on the very last page, there’s this: a letter from Otto Nathan, a good friend and the executor of Einstein’s will, informing the two sisters that Einstein left instructions that he will pay all their tuition, travel, and accommodation expenses for them to study music at the Royal Academy in England, which their family couldn’t afford. But we know what was in Einstein’s will and this gift was not there. Thus, here is a detail that can be checked as being false. As such, I would say this stretches too far the boundary of the genre.

The second Einstein novel is A Solitary Smile (Beeline Press, 2019) by Yours Truly. The novel takes place in a single day – March 21, 1955 – less than a month before Einstein’s death. He has been informed of the death of his best friend, Besso, and he is compelled to write a condolence letter to Besso’s family. The novel’s setting is entirely within Einstein’s study in his home in Princeton, where he is living with Helen Dukas and Margot Einstein. During the day visitors come and go, such as Oppenheimer and Nathan. As Einstein attempts to compose the condolence letter, he reminisces about his life: thinking of the past, daydreaming, dozing off and having real dreams, and having imaginary conversations with Besso and others from his life.

There are 5 chapters: 1) late-morning; 2) mid-afternoon; 3) late-afternoon; 4) evening; and 5) late-night. Each has a common theme. For Chapter 1, it’s the women in his life. Chapter 2 is on his struggles with his Jewish identity. Chapter 3 looks at his social and political views. Chapter 4 has two parts: first, he recalls his entire scientific career, while listening to Mozart’s Requiem; and, second, he finally drafts the condolence letter. In Chapter 5 he wakes up in the middle-of-the-night, cannot go back to sleep, and goes into his study. Here the reader finally discovers the meaning of the title of the book.

Some of the other highlights in the book are: a long dream of being caught up in the Holocaust in Chapter 2; a chat in Chapter 2 with his gardener about the endemic racism in America; conversations in Chapter 3 with Oppenheimer and Nathan on political topics relevant to post-war America; a dream in Chapter 3, of being called before the HUAC committee, and accused of being a communist. Everyone in the book is real, except for the gardener, and much of the dialogue is directly or indirectly from documented sources. The result is an historical novel that is concomitantly a short history of Einstein’s life, in this case presented thematically.

Gadney’s book and mine, being seemingly the only two novels on Einstein, at least in English – it’s a pleasant fact that they complement each other in several ways. So, in short, it seems, the so-called plethora of novels on Einstein, which will complement those already on Cleopatra, numerous Roman emperors, Henry VIII, Queen Elisabeth I, Napoleon, and all the other historically famous people, has barely begun.

Books Cited:

Alice Calaprice, The New Quotable Einstein (Princeton University Press, 2005)

R. J. Gadney, Albert Einstein Speaking (Canongate Books, 2018)

Alan Lightman, Einstein’s Dreams (Warner Books, 1994)

David R. Topper, A Solitary Smile: A Novel on Einstein (Beeline Press, 2019)

Albert Einstein and the high school geometry problem

The famous physicist’s answer to a Hollywood high schooler’s letter went viral 65 years ago.

David Topper & Dwight E. Vincent

Physics Today (People & History), December 19, 2017

https://physicstoday.scitation.org/do/10.1063/PT.6.4.20171219a/full/

In a Note (Feb. 11, 2019) from the editor of Physics Today we were informed that

this article was the 2nd most popular on-line and the 4th overall for 2018.

Since the editor of the Physics Today journal edited out the biographical part of our paper,

I have added this story below, because I think it will be of interest to most readers.

Born on October 2, 1937, Johanna was the daughter of Herman Mankiewicz, a writer, who collaborated with Orson Welles on the movie Citizen Kane. His brother was Joseph Mankiewicz, the famous producer and director, and hence Johanna grew up in the atmosphere of Hollywood, with Jane Fonda as a childhood chum. Since she was living within the world of notoriety and stardom, I wonder how much the idea of writing a letter to Einstein was of her own volition, and especially whether she alone initiated the press photos and interviews. Of course, we can only leave these as probably unanswerable questions.

Her brother was Frank Mankiewicz, who went on to a career in journalism and became involved in politics. He is best remembered as Robert Kennedy’s press secretary, who announced Bobby’s death to the press after the assassination on June 6, 1968. His son, Ben, is the TV host on Turner Classic Movies.

After High School graduation, Johanna went east to Wellesley College where she met and married a Harvard University student, Peter Davis. They had two children, and she started a writing career, eventually working for Time magazine, and even publishing in 1973 a novel, Life Signs. The book was well received by reviewers, and even spent some time on the NY Times best-seller list. As her career was taking off, so was that of her husband, who was working in TV and movies, focusing on issues of social conscience. Indeed, he went on to win an Oscar for his feature documentary on Vietnam, Hearts and Minds (1975), which is considered a classic today by many film buffs. Davis’s acceptance speech on April 8, 1975 before the Academy, however, was bittersweet. The previous year, on July 25, 1974, Johanna was walking in their neighborhood of Greenwich Village with their 11-year-old son, Timothy, when she was struck by a taxi and pinned against a mailbox. She died at the age of 36. Timothy was unhurt (LA Times, July 27, 1974, p. B3).

I recently came across a website trying to revive her novel, calling Life Signs a neglected book. I read Life Signs, and found it partially but plainly autobiographical: the main character (Camilla) lives in New York, but she grew up around Hollywood; her father is a movie writer and her Harvard-graduate husband makes documentaries. The book is smartly written and both witty and bleak. Haunting the text for this reader, needless to say, was the knowledge of Johanna’s shocking death. Yet I still broke out with a chuckle when Camilla said at one point that “she had always been good at math,” but I discernibly felt a deep chill when Camilla was crossing a street in New York and she was almost hit by a truck.

A Note on Einstein’s Dreams, by Alan Lightman (1994):

Or, why this book is not an historical novel about Einstein

Lightman’s little book is beautiful but strange. It is set in 1905 Berne, when Einstein was working in the patent office with his best friend Michele Besso. It consists of 30 very short chapters, dated from April 14 to June 28, each being a dream about a world with a different concept of time. In addition, there is a Prologue, three Interludes, and an Epilogue. (I should point out that it was during this period of Einstein’s life, specifically from March 18 to September 27, that he submitted his four revolutionary physics papers to the German Physics journal. In particular, on June 30, he sent the first paper on relativity that put forth his new theory about time.)

In the Prologue, Einstein is waiting for a secretary to arrive, since he has a paper on relativity for her to type. In the Epilogue, he gives her the paper.

In the Interludes, Einstein is with Besso: going for a walk, in a café, and fishing from a boat in the river. In these episodes, Einstein is absent-minded, even moody, distant, and almost incommunicative. There is very little real engagement between them – this, despite the fact, that Einstein thanked Besso, and only Besso, for his help with the paper on relativity. (Lightman does not mention this.) Importantly, there is no discussion about the concept of time between them, even though historians have evidence that something Besso said was a catalyst for the idea of the relativity of time. (Lightman does not mention this, either.) Also, there is a brief mention of Einstein’s wife and son, but otherwise nothing on his life.

In the 30 chapters of dreams, different concepts of time are considered. For example: time going in a circle, time standing still, a world without time, time going backwards, a world where people live forever, a world without a future, and so forth. Only one dream, on May 29th, where time slows down as people move faster, has any relevance to Einstein’s theory.

Now, importantly, there is no evidence that Einstein ever considered the other 29 concepts on his road to relativity, nor that such ideas would even emerge in terms of the problems he was working on. I find this all extremely odd. Lightman could have carved out these lyrically written fantasies about other worlds with other times, without bringing in Einstein. That’s why I call this book beautiful but strange. Why he wrote it this way, I do not tknow.

Moreover, the scope of the novel is only this very short period (two months, however important they were) in Einstein’s life. I therefore cannot categorize this little book as an Einstein novel in any meaningful sense of the term. It is more fantasy than history. It least, it certainly cannot be considered an Einstein novel in any comprehensive sense.

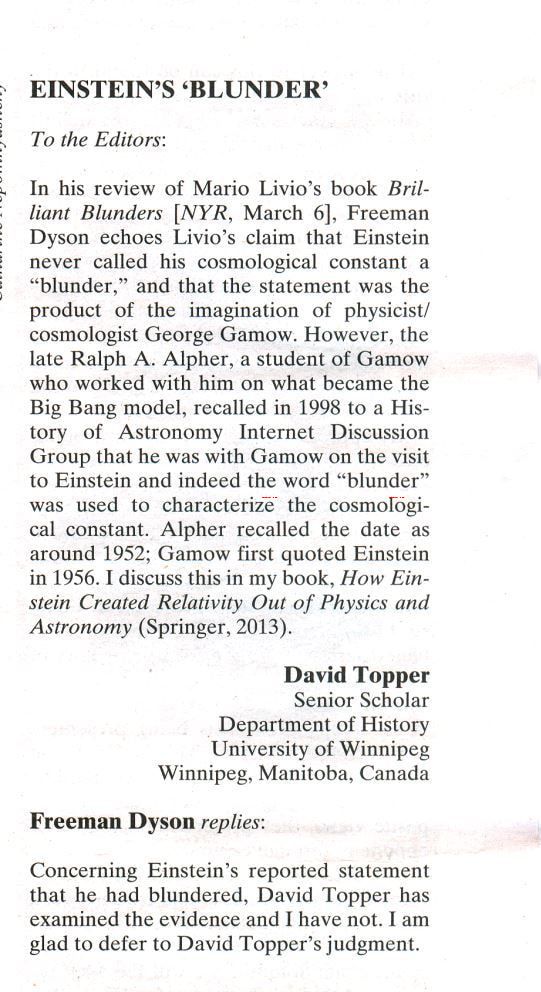

This Letter to the Editor

appeared in the

May 8, 2014 issue of the

New York Review of Books.

appeared in the

May 8, 2014 issue of the

New York Review of Books.